|

Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume

7, Issue 2, Article 1 (Dec., 2006) Shu-Chiu LIU Historical models and science instruction: A cross-cultural analysis based on students’ views

|

Students’ models of the universe

In attempt to discover students’ alternative conceptions of the universe, Liu (2005) conducted an investigation with third to sixth graders (8-13 years old) in Taiwan (n=32) and in Germany (n=32) by means of interviewing in a story form. These students were randomly selected from a primary school (for Grade 1-6) in Taiwan and a Grundschule (for Grade 1-4) and a Gesamtschule (similar to comprehensive school; for Grade 5-12 or 5-13) in Germany; all of the schools are typical in terms of school size and student population and located in middle-sized cities. The age range was chosen for the fact that formal instruction on this subject is not given yet, and students may likely harbor a different view from the scientific one. They probably received previously related information from various sources, such as media and adults, these information may however be “internalized” based on their personal knowledge and thus given a different meaning. Consequently, these students may present a view that is not yet re-shaped by formal instruction and should be taken into consideration upon instructional design.

The interview was conducted individually and took for each 30-40 minutes. The participant was asked at the beginning of the interview to play the role of an Earth child and to have a conversation with an alien child (played by the interviewer) who by chance falls onto the Earth. A number of questions were presented in the interview, concerning the Earth (its shape, motion, relative positions to the obvious celestial bodies, etc.) and the heavens (its meaning, characteristics of the heavenly bodies and reasons for day/night cycle and the Moon phases). They were intended to reveal not only verbal responses but also students’ drawing, clay model making and demonstration using clay. The data were analyzed using a similar technique documented in several studies on students’ mental models (Nussbaum, 1985; Vosniadou & Brewer, 1992, 1994). The main results of the study are summarized as follows (for a detailed discussion of theoretical and methodological issues, see Liu, 2005):

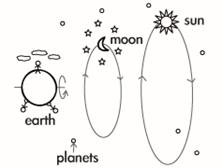

1. In accord with the previous studies in conceptual change research (to name a few examples: Carey, 1987, 1988; Vosniadou, 1991, 1994; Coll & Treagust, 2003), the elicited knowledge of Liu’s students exhibits a structural form. Their ideas about the Earth and the sky seem to be rooted in a model of the universe, which is to various extents different from the accepted scientific one. A limited number of such models are identified. For example, Yu-Ting, a sixth grade girl in Taiwan, holding a model (see Figure 2) in which the Sun and Moon move in two parallel vertical orbits aside the Earth with their common focal point on the line of the Earth’s rotation axis. In her model, the Earth rotates with an imaginary horizontal axis. There are clouds situated above it. Many cosmic bodies scatter in space. The Sun and Moon are those close to the Earth in the heavens, yet none of them is a cosmic body – they are something different from other things in the sky-, according to Yu-Ting. Although she knows that people can live at the bottom of the Earth, without falling down to the space, thanks to gravity, she believes that gravity is a force produced by the atmosphere and a property unique to the Earth. Her view indeed shows an emphasis on what one sees and where one locates. This is not novel among students, nor in history of science.

|

| Figure 2. A model presented by Yu-Ting (Taiwanese 6th-grader). |

2. Virtually all students know that the universe is infinite. However, further interrogations disclose a tendency that the students confine the basic astronomical objects – the Sun, Moon, Earth, planets and sometimes stars - to an observable (or imaginary) space and thus there is often a center of either the Sun or Earth. The described relative distances among the Earth, Sun, Moon, stars, and the “remote” stars indicate a separation of an observable space, where most, if not all, objects are situated, and the remote outside vastness, which seems to be beyond discussion. This approach to viewing the sky seems practical and plausible in that it is derived from a sensory experience of sky watching. The early Chinese scientists had inquired into the sky in a similar manner.

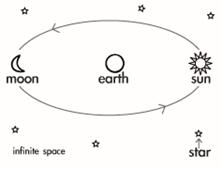

3. There are a limited number of models presented by the students; they can be grouped into Earth-centered and Sun-centered views. This finding is not surprising as children’s egocentric view is well recognized among educational and psychological researchers. The most popular model of Earth-centered group is illustrated in Figure 3, in which the Sun and Moon, and sometimes even stars, revolve the Earth. In contrast, students with a Sun-centered view most frequently entertain a model in which the static Sun is located in the center (Figure 4). These two views can immediately draw our attention to history of science; to consider either the Earth or Sun in the center of the universe, as well documented, has been a crucial point in scientific thinking in the Western world.

|

| Figure 3. Earth-rotating heavens. |

|

| Figure 4. A model with static Sun in its center. |

4. Similar to results of previous studies (Nussbaum, 1979, 1985; Vosniadou, 1991, 1994), some students, in particular those with Earth-centered view, have difficulty in relating the flat Earth as viewed on the surface of the Earth to the spherical Earth as explained by other people. The difficulty gives rise to statements like “clouds are located (only) above the Earth”, and “people cannot live at the bottom of the Earth”. As well acknowledged, the idea of a flat Earth had been common among people in the ancient world.

5. Comparing the data from the two countries, it is found that the Taiwanese students appear to have less intention, and sometimes even do not see the need, of reasoning celestial phenomena. When asked to explain the causes of day/night cycle and phases of the Moon, they often appear as if these questions were unusual or simply never came to their mind, while their German counterparts seemed to be prepared to answer these questions, correctly or not. Especially worth-noting is the comment from several Taiwanese children that there is no reason for the phenomenon in question: These events act as the way they are. While these Taiwanese children constructed relatively primitive models compared to the others, it can be argued that the position of “reasoning” plays a role in refining their models. This connection can be also traced in history of science.

Copyright (C) 2006 HKIEd APFSLT. Volume 7, Issue 2, Article 1 (Dec., 2006). All Rights Reserved.