Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, Volume 21, Issue 1, Article 2 (Dec., 2021) |

The Covid-19 pandemic affected the education sector worldwide as indicated by its influence on 1.2 billion children and youth in 200 countries, including Indonesia (UNESCO, 2020; Reimers, 2021). This led researchers, administrators, and teachers to ensure the continuation of education using online platforms with digital or digi-pedagogy systems (Reimers, 2021). The digi-pedagogy aspect involves the knowledge and skills used as digital tools and platforms or digital environments for online learning (Greenhow et al., 2020). The selection of the appropriate system is expected to assist teachers with instructional design, digital tools, and platforms to support student learning, engagement, and well-being.

This digi-pedagogy was observed to strengthen the conduct of online learning by educators but requires some level of creativity in delivering the learning materials. It is important to note that the current learning resources are very varied, thereby, making them very easy to use in studying science and solving problems (Suwandi et al., 2013; Putranta et al, 2019). This is considered necessary to fulfill the rights of the students to learn and also assists the educators in achieving the contents of the curriculum. This indicates the application of online learning needs to be combined with fulfillment of the contents of the curriculum in order to prepare the next generation and ensure they have life skills applicable in their era, the 21st century. This, therefore, makes the determination of the effectiveness of online learning to be very important in line with the opinion of Nieveen et al. (2007) that educational activities of educational institutions need to be effective.

A significant example of 21st-century life skills is critical thinking which has been observed not to be growing and developing naturally with an individual’s physical and psychological development but through training and education. This denotes it needs to be acquired through formal, non-formal, and informal education, and it is considered important because it is required to understand the challenges of an increasingly complex and rapid future development era (Gumus et al., 2013; Akhdinirwanto et al., 2020). Therefore, it can be concluded that critical thinking skill is one of the factors supporting successful learning for future success.

Critical thinking is one of the basic skills needed to develop knowledge through the ability to ask questions, make observations or experiments, collect data, analyze, synthesize, and conclude to gain new knowledge and apply it in real life (Meredith & Steele, 2011; Akhdinirwanto et al., 2017; Munandar et al., 2018) It is considered important because it provides opportunities for students to learn through observation. According to Redhana (2012), critical thinking skills are at the heart of the future of all societies around the world with their indicators explained by the Revised Bloom's Taxonomy (RTB) to include analyzing (C4), evaluating (C5), and creating (C6) (Rukmini, 2008; Ruwaida, 2019).

This definition shows that a person with the ability to think argumentatively through the inclusion of the following three factors has critical thinking skills. First, being able to respond to problems and question them in depth in order to avoid the habit of receiving unidirectional information without first questioning the information, second, knowing several methods of thinking, and third, having the skills to apply these methods. These three factors can be achieved by an individual with analytical reasoning, evaluative reasoning, problem-solving, and argumentative abilities (Shavelson, 2010). Analytical reasoning is the ability to solve a problem by breaking down complex and comprehensive information into basic and principal parts by gathering information, identifying problems, and finding solutions. Meanwhile, evaluative reasoning refers to the ability to judge whether an action is good or bad or an idea is founded on certain criteria that do not change the idea. Problem-solving skills refer to the process of drawing conclusions based on logical and valid arguments while argumentative skill involves building logical and organized arguments to convince others to believe one’s opinions.

A previous study by Maslakhatunni'mah et al. (2019) showed that the critical thinking skill of students in a junior high school in the city of Wates, Kulon Progo is in a low category. It was observed that the (1) students were less thorough in the process of analyzing problems, (2) had difficulties working on high-level questions (C4-C6), (3) some were unable to the assignment, (4) had difficulties connecting concepts and problems, and (5) had difficulties in expressing their opinions during discussions. These findings were supported by tests containing the indicators of critical thinking skills (Rukmini, 2008; Ruwaida, 2019) in grade VII which showed that 50% analytical skills were acquired, 52% evaluation skills, and 42% creative skills. This implies low critical thinking skill in secondary schools is a problem requiring immediate attention (Aun & Kaewurai, 2017).

Previous studies have recommended methods of improving critical thinking skill such as the application of three types of learning models (Fuad et al., 2017), simulation models of higher-order thinking skills (Saputri et al., 2019), and through argumentative activities and analysis of ideas and questions delivered by the teacher (Cotrell & Cotrell, 2005). The use of learning models was observed to be the easiest way and mostly demanded by teachers due to the possibility of implementing them directly during the learning process (Husamah et al., 2018).

Argumentation originates from Latin and it denotes expressing opinions based on scientific proof. The concept was also defined by Emeren et al. (2004) to be a social and rational verbal activity developed based on intellectual considerations to convince a critique about an opinion by proposing a constellation of prepositions to justify or refute a particular proposition. Moreover, Besnard and Hunter (2008) defined argumentation as an activity to identify relevant assumptions and conclusions from a problem being analyzed and identify conflicts in order to accept or reject certain conclusions. It was also explained by Toulmin (2003; 2012) to be a statement accompanied by reasons and its components which include claims, data, evidence, support, qualifications, and refutation. These definitions showed that argumentation is a serious effort to convince or prove the truth of an idea, attitude, statement, or action to a particular audience using facts to make them believe the information.

Argumentation is one of the most important skills required to be possessed by students studying science in order to allow them to generate new knowledge, either in the form of new theories, new ways of collecting data, or new ways of interpreting old data (Osborne, 2010; NRC, 2012; Eskin, 2013; Wang, 2016; Wardani et al., 2016). The first reason for science students to acquire this skill is to learn the methods of solving problems gradually, second is to build socio-cultural activities through the presentation, criticism, and revision of an argument, third is to make it easier and more daring for them to express their ideas due to the existence of supporting evidence (Farida & Gusniarti, 2014), fourth is to make it easier for the students to understand concepts and reason because the evidence to support the claims need to be sought independently by them (Handayani & Sardianto, 2015), the fifth is to use the critical and logical thinking skills regarding the relationship between concepts and situations associated with argumentation to explain the facts, procedures, concepts, and settlement methods that are interrelated (Soekisno, 2015: Fatmawati et al., 2018), and sixth is to serve as an important factor in reaching the agreement on the right solution to a problem. This, therefore, shows that students with the courage to express their ideas usually have the ability to increase their intellectual development and critical thinking skills (Oh & Jonassen, 2007; Surif et al.; 2012; Wardani et al., 2016).

These reasons showed the suitability of applying argumentation in science learning considering the fact that arguments are needed to explain the principles and concepts of science and the relationship between them. The argumentation model trains the students to make claims based on data and evidence as well as theories to support these claims (Rabertshaw & Campbell, 2013; Siregar & Pakpahan, 2020). According to Toulmin, scientific arguments include data, evidence, support, justification, refutation, and claims which are known as Toulmin's argumentation pattern (Kulatunga et al., 2013; Akhdinirwanto et al., 2020). Moreover, data is used as evidence to obtain claims while justification connects data and claims, and refutation is observed when a claim is rejected. The ability to use the argumentation model is expected to improve students' critical thinking skills.

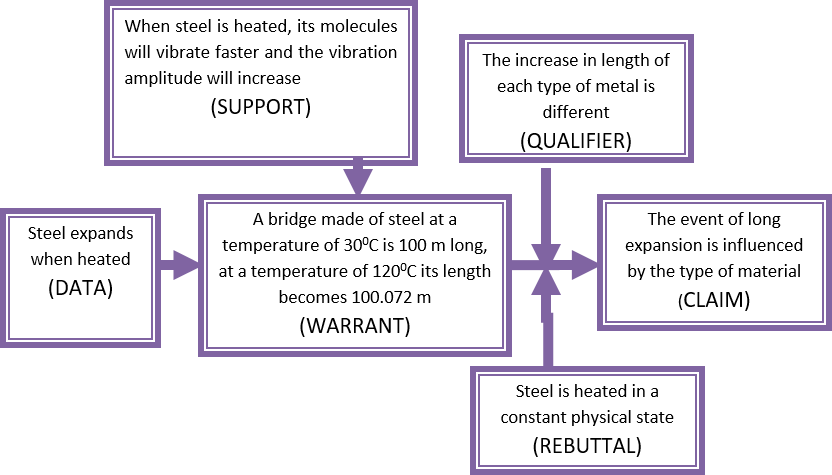

An example of Toulmin's argument application in science problems is as follows.

A bridge made of steel at 30oC is 100 m long. What is the increase in the length of the steel when its temperature rises to 60oC? What is the length of the bridge at 120oC (coefficient of expansion of steel length = 0.000012/oC)?

The question first needs to be resolved as follows before applying Toulmin's argument:

Known variables:

The initial length of steel = 100 meters, initial temperature of steel = 30oC, final temperature of steel = 60oC, and the coefficient of expansion of steel length = 0.000012/oC.

Asked:

1. Increase in the length of the steel bridge 2. Length of steel bridge at 120oC

Answer:

- Δt = t - to = 30 l

Δl = loαΔt = 100 m . 0.000012/oC . 30oC = 0.036 m

- Length of steel bridge at 120oC = 100 m + 2(0.036 m) = 100.072 meters.

The solution was described with Toulmin's argument as follows:

Figure 1. Toulmin’s argument pattern for the long expansion of steel.

The use of argumentation in learning strengthens the mastery of the concepts in the material being studied and also improves critical thinking skills (Berland & Lee, 2012; Akhdinirwanto et al., 2020). It is, however, important to note that the online argumentation learning was implemented through the reverse learning approach in the form of the Flipped Learning (FL) model due to the fact that the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (Akhdinirwanto, 2020).

This reverse classroom approach involves the delivery of learning content on a digital platform with the students required to learn the subject matter provided by the teacher by downloading the content on YouTube before the teacher teaches. This infers the video is the medium often used as the input to conduct independent study and is usually applied based on the needs of the students due to the fact that it can be stopped and watched again. Moreover, text and audio can also be used to convey material and ensure students' readiness to conduct synchronous learning because they allow the students to choose the time to study, ask questions through the comment section, and share the ideas and their understanding of the material being studied with the teacher and their colleagues in the class. It is also important to note that the feedback is not received collectively but individually.

The activities normally conducted in the classroom such as the delivery of subject matter, assignments, training, and homework are transferred online in the flipped learning model. The students listen to the teacher's explanations and receive online practices at different physical locations connected through information technology devices. This implies the learning is student-centered with the students required to conduct independent learning.

The steps in the FL model include the preparation or pre-class, in-class activities, and post-class activities (Kong, 2015; Adhitiya et al., 2015). In pre-class activities, students are asked to download learning materials uploaded by the teacher on YouTube or other social media. In classroom activities, teachers and students meet in online classes to discuss learning materials downloaded by students. In post-class activities, students are asked to apply the learning outcomes from the online class.

This study was, therefore, conducted to determine the effectiveness of the argumentation-flipped learning model in improving the critical thinking skills of junior high school students. The specific research problem formulated was “how effective is the argumentation flipped learning (AFL) model in improving students' critical thinking skills?”

Research problem

The main problem designed to be answered by this research has been stated and the AFL model is adjudged to have the ability to improve student's critical thinking skills when it satisfies the required validity, practicality, and effectiveness. Meanwhile, the validity was determined using content and construct validities which are declared valid when the statistical analysis of the percentage of agreement (R) is above 75% (Borich, 2016), which is also required by all learning tools. The practicality was determined when all the syntax of the model can be implemented effectively, the students have the ability to conduct the activities efficiently, the obstacles during learning were overcome (Pandiangan, Sanjaya, Gusti, & Jatmiko, 2017), and the statistical analysis of the percentage of agreement (R) is above 75%. The effectiveness factor is determined when the students experience an increase in the critical thinking skills of at least 50% of those discovered to be in the low category with the normalized gain (n-gain) recorded to be above 0.3 (Hake, 1999; Pandiangan, Sanjaya, Gusti, Jatmiko, 2017).